I’ve been spending some time thinking about the long term implications of increasing central bank intervention (primarily the US Fed), and how that changes the landscape of banks and fintech. What follows is an attempt to flush out an idea of how Fed intervention is good for fintech in the long run.

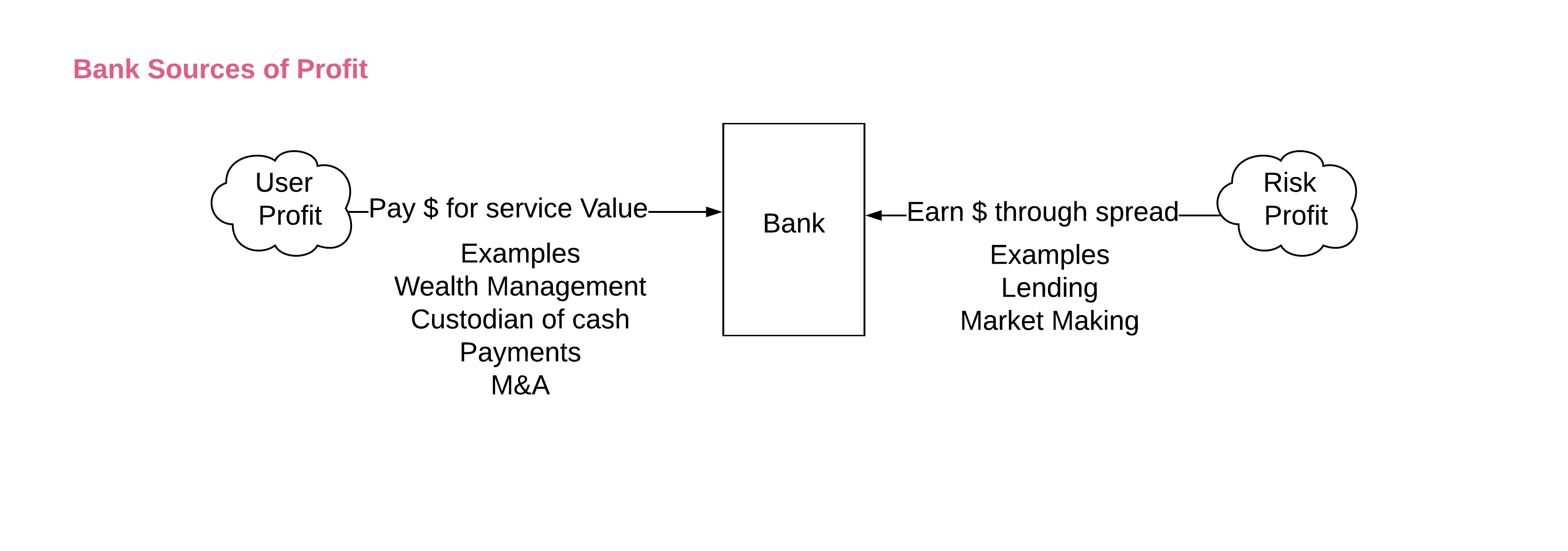

I have a simple framework to think about how banks work. Banks have two sources of profit, user profit, and risk profit. User profit is what customers are willing to pay for services that provide value. Some examples are, charging for managing your investments, the entire process of giving you a loan (origination fee), converting currency, processing payments, etc. Risk profit is what banks earn by the nature of providing maturity transformation and inventory facilities. Some examples are loans (compensated for taking credit risk) and market-making (compensated for taking inventory risk).

The process of earning a risk profit is the major source of systemic risk in the capitalist model. In the modern world, people and governments want to have a say in the entire risk process as unfettered capitalism hasn’t worked out in the past (Roaring 20’s and then the great depression being the most recent example). Hence risk-taking is regulated. A valid conclusion then is that regulation is the only thing that affords the ability to earn a risk-return. Regulation is the competitive advantage for a bank and also a barrier to entry for others.

On average, the absolute dollars earned in risk profit are far greater than user profit as banks have more opportunities to earn risk profits using leverage and sophisticated financial engineering techniques. So rightfully so, this has been their focus. As a consequence, banks neglected their ability to innovate on the user side and instead spent a lot more time on the risk profit side. Most of their effort went into building backend systems and compliance systems to take advantage of and maintain their regulatory advantage. Users became a second class citizen.

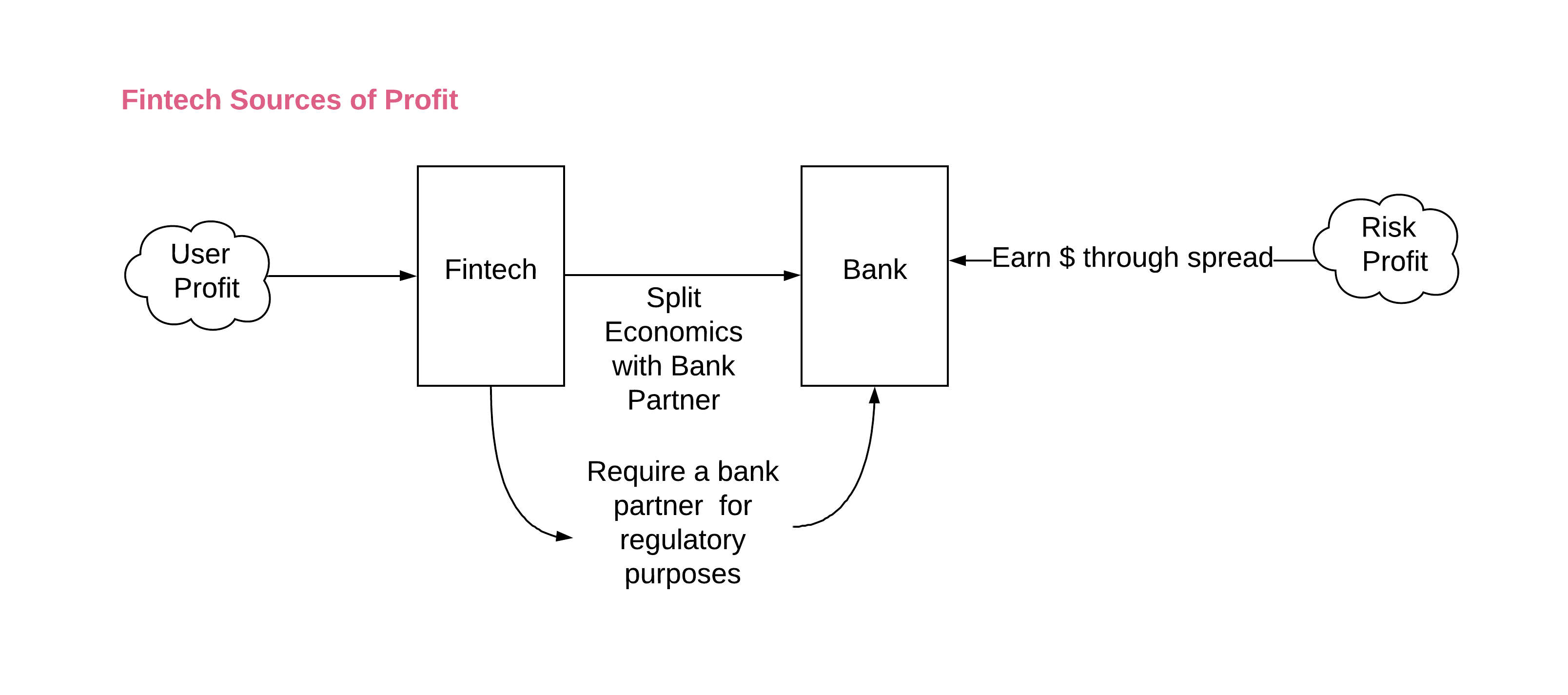

New startups in finance aka fintech follow a similar framework, except that they have limited or no ability to earn a risk profit. The trade-off for fintech was – should I become a bank? , which is a long drawn out process, or get started quickly with a bank partner. Every fintech has gone down the partner route i.e chosen to get started first and faster. Fintech was born on the internet where the (correct) prevailing philosophy is that users come first. Aggregate the demand and you can build big businesses. This makes sense in this framework – banks are more interested in risk profit and have taken the eye off the ball on the user side. Let us, using VC funding focus on the user end and eventually, as we aggregate the entire user base we can start making a user profit. Since we have all the users, risk profit will eventually follow.

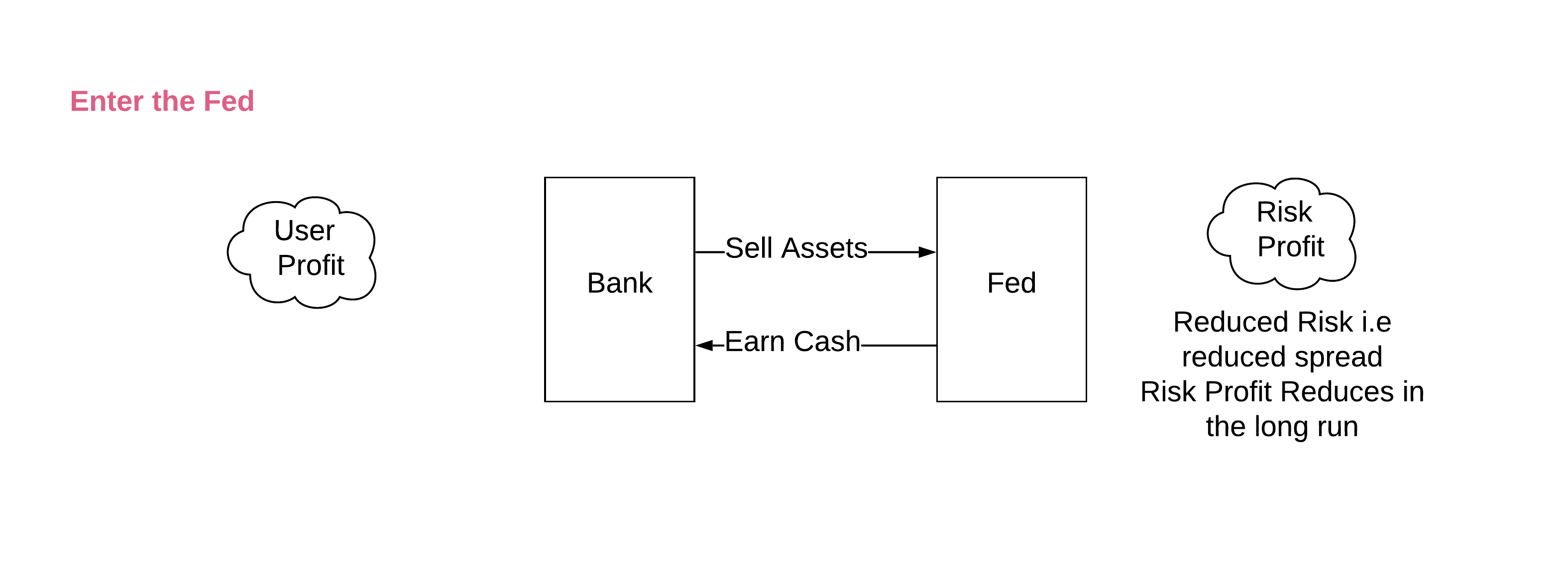

Lets now add a third very important player into this equation, the central bank. In the US it is the Fed. But first a slight detour into why the Fed exists. Financial systems from time to time suffer from liquidity problems and the central bank concept was invented to provide a solution to this liquidity problem. The root cause of the liquidity problem is the fractional reserve system that we live in. The central principle in a fractional reserve system is that every person with assets (cash primarily) does not need access to all of it at the same time. Let us walk through an example to make it concrete. Say you have $100 and you want to keep it in a safe place that is not your mattress :). You go to a bank and deposit the $100 with them. You need access to this $100, but in the future i.e you are not going to take out the $100 from the bank the very next minute you deposited it. So, in theory, the bank doesn’t need to always keep the $100 in its bank vault, it only needs to make sure that when you come by in the future and ask for it – it has to return $100 back to you. The bank can put a probability on that number and say that on average only 10% of the time you need that money the next day. So effectively it only has to “reserve” $10 of that $100. On aggregate over a large deposit base that reserve requirement takes care of meeting the everyday withdrawal demands of cash. Now you have $90 of cash that is sitting idle in the bank, the bank can put that money to work by lending it out. Say the local small business (SMB) wanted some capital to expand, and the bank lent it the $90. The bank made that loan because it is in the business of making a risk profit. The SMB will get charged an interest rate (say 10%), some of it will be passed on to you as a depositor (say 1%) and the bank will pocket the difference (9% the spread). This is a simplified example of how reserve banking works and how banks earn a risk profit.

Now imagine that you have lost your job, you want all of your $100 back immediately. You go to the bank and ask for your $100 back, however, the bank only has $10 as its lent $90 to the SMB. The SMB is under no obligation to pay it back right now, in fact, he has to pay it back in 5 years. Before the Fed existed, the bank would just close up shop and the depositor is screwed, you lose your money. This is what happened in the Great Depression. In response to the bank failures in the great depression the Fed was created and the discount window was born. Think of the discount window mechanism as an actual window where a bank can go and talk to a Fed banker and conduct business. With the Fed in the system, now when you go and ask for $90 from the bank, the bank can turn around and pledge the loan that it made to the SMB as collateral to the Fed and get $100 from the Fed i.e borrow from the discount window. It has the full $100 in hand and can return it to you. Since there is nobody who is going to ask the Fed for its money back (its the US government), the Fed can wait for the SMB to pay down its loan and become whole (i.e get the $100 back). Thus with the discount window mechanism, the Fed stabilizes the system by providing liquidity. One key assumption here is that the SMB loan that is pledged as collateral is of sufficient quality. The Fed is not in the business of taking credit risk. It does not want to deal with trying to collect from a borrower who is behind on his payments. So the Fed only accepts government securities (T-bills) as collateral. Government T-bills have zero credit risk.

Enter 2008. In the GFC the Fed had to start stabilizing the entire financial market and stepped into the mortgage market. It started accepting Mortgage-backed securities as collateral to inject liquidity into that market. Fast forward to 2020, in the coronavirus crisis the Fed expanded its collateral mix again to accept High Yield bonds and PPP loans. It has also set up a lending facility to directly lend to companies So, with every crisis, the Fed seems to be expanding the collateral mix of what it is willing to accept. Now let us introduce the Fed into our model.

With the Fed increasing the envelope of the types of collateral it is going to accept, it is in the short term, driving up the risk profit of banks, but shrinking it in the long term. It sounds counterintuitive, but here is the logic. In the short term by accepting a wide range of collateral, the Fed is taking the risk out of the system. This makes the bank’s risk profit essentially risk-less. In the short term, the bank is pricing the collateral as if its a risky asset but then parking it at the Fed to get a riskless profit at the original risky price! That’s a good markup, so in the short term, profits are up. Following our SMB example, at the time of the origination of the loan the interest rate was set at say 10%, the bank parks the loan at the Fed and earns a riskless 10%. However as time goes on, the Fed being a government entity and taxpayer-funded to an extent, will start putting pressure on banks. The logic being, the Fed is supposed to serve the people and since you are in effect using the Fed to make a riskless profit, you have to charge the end-user less. So in this regime, the SMB loans originated should have something like a 2% interest rate. There will be huge political pressure to go down this route. Since the Fed cares more about stabilizing the system and welfare of the economy, it will gladly compress the risk profit for banks. Thus in the long term, this will reduce the risk profit for banks.

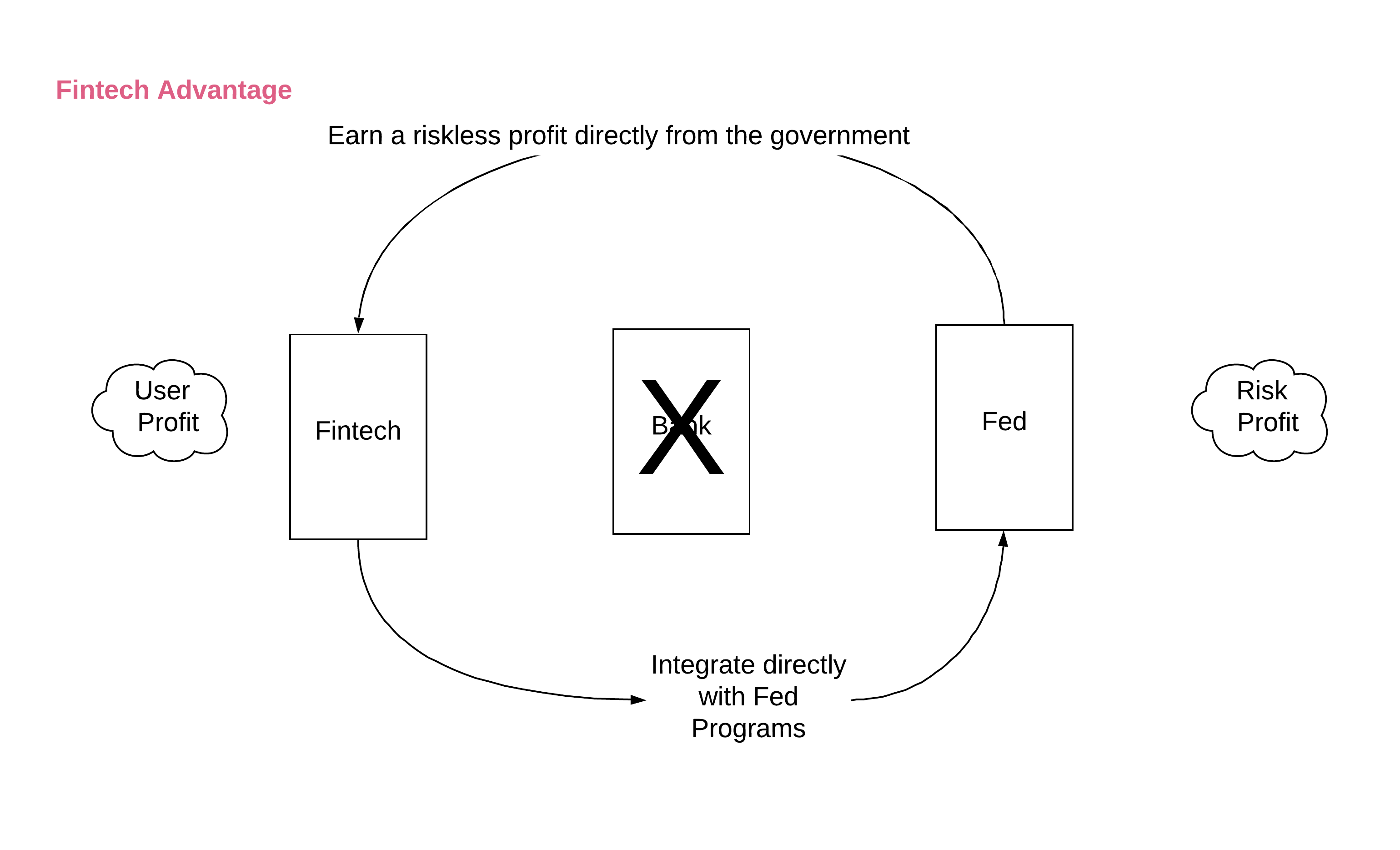

If my thinking is correct, this trend is long term good for fintech. The next source of competitive advantage for Fintechs is direct access to the various Fed programs. By connecting directly to the Fed (partially or fully) fintechs can outflank banks. Fintechs have an advantage on the user profit side and by connecting directly to the Fed they can greatly reduce the need for a bank partner and fully capturing the economics on the risk profit side. Even if in aggregate, the risk profit is reduced due to the intervention of the Fed, it is still big enough for fintechs. The overall pie may be reduced, but fintechs can take a large piece of the smaller pie at the expense of the banks. In absolute dollar terms, It is still way bigger than the piece of the pie they had with the bank in the middle.

So what should you start focussing on as a forward-thinking product manager? Strategically it becomes important to start building the muscle of figuring out the various government programs and how can you connect to these programs.

- Do I know at a deep level how the government banking system works?

- What are the data requirements and formats that the Fed needs to onboard assets into their collateral facilities?

- What are the audit requirements that certify this collateral as acceptable?

- What ongoing monitoring does the Fed need of these assets and how can you provide this to the Fed in the format they want

- Of the assets that you originate what are some unique ways of packaging it so that it fits the model of how the Fed thinks about acceptable assets?

- How can you build software that automates all the above?

Think ahead, be prepared, its a brave new world!

Great article Rohit. It’s always good to continually learn more about our systems.