Ayden was the next pick for the Fintech PM guild’s next 10k session. As I dug through their financials, I realized that I wasn’t familiar with the history of the business they were in. Why does merchant acquiring exist as an industry? What is the history of this business, why does it exist the way it does today? Let us take a step back and take a walk through memory lane.

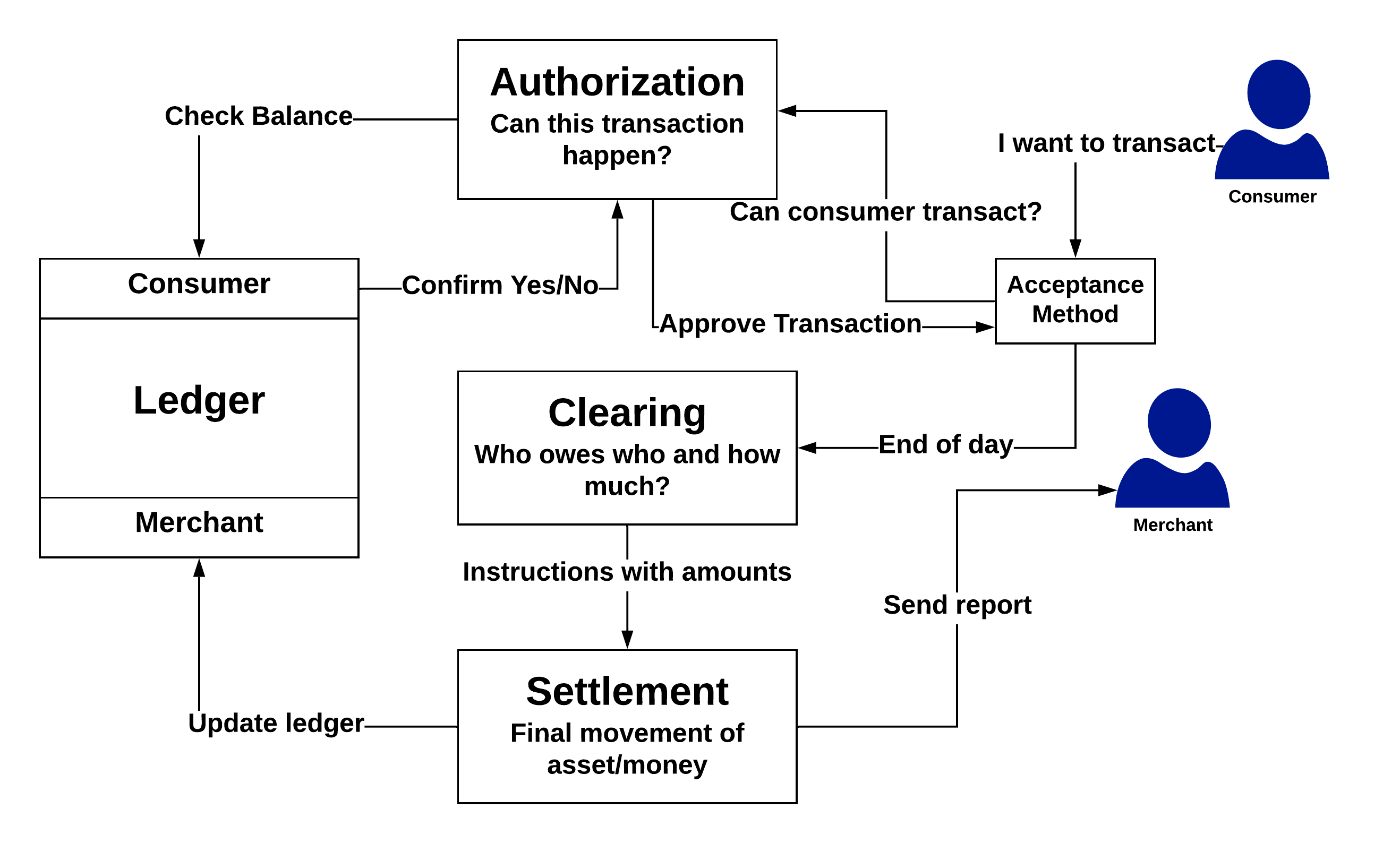

To understand any system it is useful to have a framework around the core jobs to be done in the system. In a payment system, money is the main asset exchanged between parties and there are three main jobs to be done.

- Authorization i.e. can this transaction happen? Does the initiating party have money and can the receiving party receive this money?

- Clearing i.e. what are the final amounts exchanged and between whom? Clearing is the bookkeeper who creates the instructions that are recorded in the ledger.

- Settlement i.e. the final transfer of money (or any asset). This is the actual transfer of cold hard cash or the final ledger entry that commits the transaction.

Early history and evolution

Let’s start with the basics: What’s the use case for a credit card? The first cards introduced to the market in 1946 were “charge” cards. With charge cards you pay your balance in full at the end of the month. The primary motivation for the charge card product was to encourage loyalty amongst the banks customers. Convenience was not the initial use case as they did not have a lot of merchants that could accept the charge card. As the product evolved, banks figured out the credit angle, and in 1958 Bank of America launched the first credit card. This is the product we are familiar with. The consumer can carry forward their balance and pay interest on it like they would on a loan. Success for the credit card product was predicated on many consumers (demand) using the card to buy goods and many merchants (supply) willing to accept this card as a means of payment for the goods that they were selling. This is a classic two-sided marketplace for which banks were the best placed to succeed. Banks were already providing services (deposits, loans, etc) to consumers and merchants so providing credit card services was a natural extension. They already had both the supply and demand side in their existing user base.

Two things to note. First, the operation of the initial product was extremely manual. Authorization happened over the phone. As a merchant, you had to call the number at the back of the card and check if the consumer had the capability to spend (available credit). The merchant then made the consumer sign a piece of paper, write down the card details and send the pieces of paper over to the bank. Then the bank would manually reconcile and calculate who was owed what i.e. clearing was manual. And finally, the bank would move money around in its accounts from consumer to merchant i.e. settlement was manual as well. This manual processing added a lot of complexity and delays which meant that the product wasn’t easier than transacting with cash.

Second, as credit was being extended, banks now had to understand how to underwrite the two distinct sets of users. Consumers were the ones the banks were most exposed to. What if consumers bail after buying a ton of goods on the card and never pay the card back?. But merchants also carried a bit of risk. The core function of the settlement process is to exchange goods for payment. As the consumer is paying the bank at least 30 days after the transaction, at settlement time (usually 2-3 days from the transaction date) the bank is the one who is actually paying the merchant. So if the merchant either goes bankrupt or fails to deliver the goods to the end consumer, the bank is exposed. The consumer transaction has to be reversed as they didn’t get the goods. It is now the bank’s problem to get its money back from the merchant. Its a short duration risk but a risk nonetheless. The key point here is that Banks are now assessing two different types of risk – Consumer risk (issuer of credit) and Merchant risk (acquirer risk). In the early days of credit cards, this wasn’t too complicated as banks were highly local and knew their customers really well (both consumers and merchants).

As a consequence of the manual operation and risk management needs, credit card products were a local affair. Your card worked only in the local geographic area that was served by your bank.

Enter Technology, the uber disrupter.

Technology always changes things :). The key barrier to adoption for credit cards was the manual auth, clear, and settle loop. The advent of the IBM computer, telecommunication networks, and the invention of the electronic Point Of Sale (POS) terminal changed all that. These three inventions automated the entire payment loop starting in 1960. A consumer swipes their card at the Merchant’s location on the POS. Using telecommunication networks the POS communicates with the bank’s IBM mainframe to check for authorization. Since all the bank account ledgers are now computerized, authorization is instant as the consumer’s balance is just an electronic field in some database. At the end of the day, the bank system can electronically reconcile, clear, and settle as it has all the transactions from the POS system. The entire loop is automated and this leads to a massive step up in credit card usage and transactions. This computerization of the whole process enables banks to leapfrog the geographical constraint. They are free to sign up consumers and merchants anywhere in the country.

With this backdrop, it is useful to look back at the needs of the two sides of the marketplace. Consumers’ and merchants’ needs are pretty divergent. Consumers cared about convenience and getting the appropriate credit limit to execute their purchases. Merchants cared about the cost of accepting credit cards, efficiency, and reporting. A classic B2C vs B2B needs split. The geographical constraint enabled banks to service these divergent needs. With this constraint removed due to technology the strain on banks intensified. They had to serve two different customer needs and with very different risk profiles.

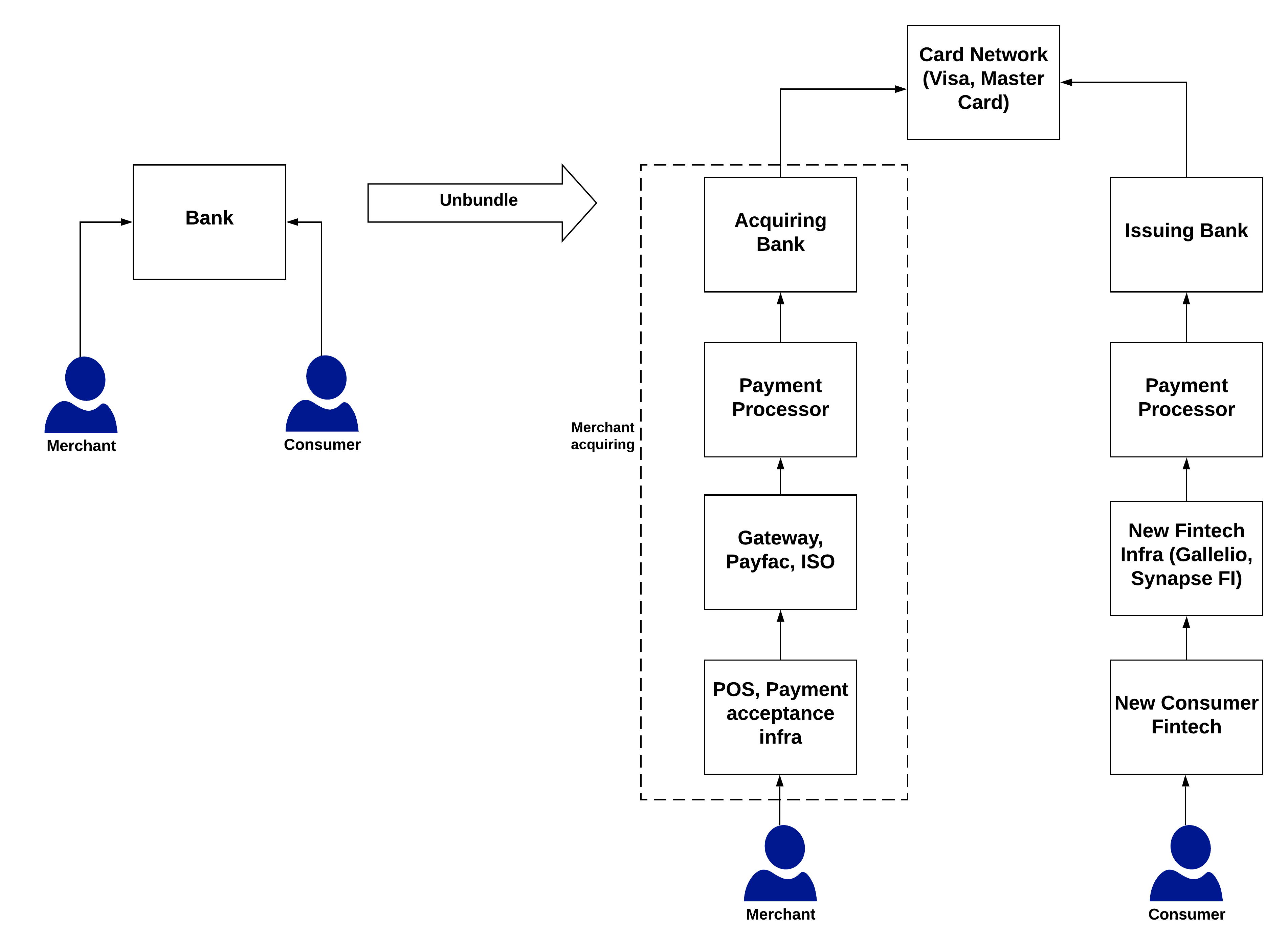

Enter the specialized merchant acquirer. In a classic case of unbundling the bank – specialized companies that were technology focussed (the tech companies of that age) started propping up to exclusively serve the merchant use cases. Enabled by technology, they competed on automation efficiency and low cost. Banks started retreating from this space as merchant acquiring become a technology play and a commodity business. Banks focussed one customer, the high margin consumer. Consumers were high margin as they paid interest on their credit card balance. The market bifurcated into banks that gave cards to consumers (issuers) and payment companies that focussed on merchants (merchant acquirers). In parallel to this bifurcation, the Visa and MasterCard card networks were also formed. The model went from a single entity playing in a two-sided network to three distinct entities each handling a particular element of the network. Banks focussed on consumers, visa and MasterCard focussed on the internal rule setting of the marketplace and providing a single ruleset for the network and acquirers focussed on the merchant side.

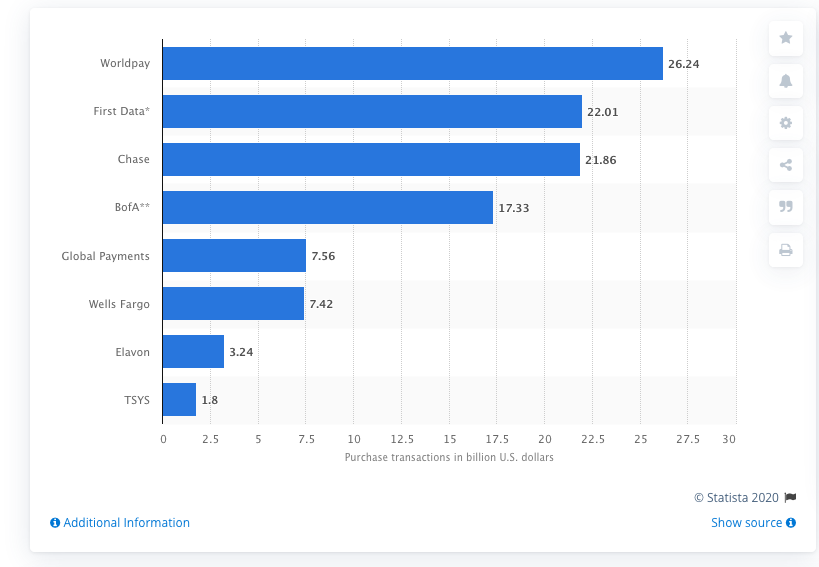

Using the framework in my previous post we can bucket the source of profit for merchant acquirers as solely user profit. The risk exposure they have to merchants small i.e there is almost zero risk profit in this business. The main value-added to merchants is card acceptance. To make card acceptance as easy as possible the entire process of auth, clearing and settlement need to be as standard as possible. Standardization always results in downward price pressures and the largest player wins. Over the years the merchant acquiring business became one of scale and commoditization. The core functions of merchant acquirers evolved into the three specific areas of marketing signing and underwriting of merchants, enabling card acceptance for merchants (physical POS infrastructure and internet acceptance via payment gateways) and clearing and settlement of transactions and the associated reporting to merchants and partners. As they got bigger the merchant acquirers themselves also started getting unbundled themselves. This unbundling has given us the alphabet soup of MSP, PSP, PayFac, ISO, etc. Initially, there were a large number of players and as the market commoditized further, consolidation took place and a few large players emerged. The largest players in the space are Chase, FIS (they acquired Worldpay), Bank of America and First Data.

Fast forward to today

As everything is fintech, we are back in the phase of the great re-bundling. Stepping back if you think about what a merchant really wants, it’s all about revenue. They want to increase their revenues across existing channels and add revenue by adding newer channels. They absolutely do not care about payment methods they can accept or how fast their transactions authorize and settle. Revenue is king and profit is the queen. They just want one company to handle this for them, one single provider that abstracts all this away and increases its revenue i.e a full-stack global merchant acquirer.

Enter Adyen.

More to follow.

Further Reading

- Origins of the VISA Electronic Payment System – Great book about the origins of the credit card

- Merchant Acquirers and Payment Card Processors: A Look Inside the Black Box– A great paper by the Fed on Merchant Acquiring

- Payments Card Economics Review – Great set of articles and papers on the history of the credit card industry

- The Merchant-Acquiring Side of the Payment Card Industry: Structure, Operations, and Challenges – Another great discussion paper from the Fed.

2 thoughts on “The history of merchant acquiring |Rise of the full stack acquirer”